- Home

- Michael Joel Green

Arresting Grace

Arresting Grace Read online

ARRESTING

GRACE

Michael Joel Green

Cover design: Jeff Still, Brian Godawa

Cover artwork: Deborah Chi

Copyright © 2012 Michael Green

All rights reserved.

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Acknowledgments

Author Bio

ARRESTING

GRACE

Chapter One

I don’t remember getting in my car to drive home. I was too drunk. The first thing I remember was being pulled over, seeing the lights in my rearview mirror. I could blame it on the beer—The Clock Cleaner—and its 12% alcohol. I could feign ignorance of the high content. But I won’t. Truth is always the healthy starting point, even if it’s the painful one. I knew I was drinking too much.

I guess the only question is why.

How many did I have, anyway? Was it two? Three? I’d like to say I stopped after two, but I could be wrong. “Stand there,” the officer instructed. “I’m going to give you a field sobriety test.” I have bad balance to begin with; I didn’t stand a chance. Moments later, handcuffed in the back of the patrol car, caught in the fuzzy haze between drunk and lucid, I realized my life was about to change. But when one is drunk, life seems more manageable.

At the station, I still had hope of getting out of it, going home without being arrested. I told the interrogating officer where I’d been that night. I was a churchgoer, godly; hopefully (fingers crossed) it would count for something.

Not a chance. I could hardly talk at the time. They keep it warm in the station and won’t give a person water. Coupled with everything else that happened, cotton-mouthed, drunk, scared, I could hardly form distinguishable words, much less be persuasive and eloquent.

“You were coming back from a church dinner? What kind of church do you go to?”

Good question. I’d probably ask the same if I was in his spot.

I remembered when my friend Nick was arrested for DUI. He said what he regretted most was taking the breathalyzer. “Always ask for a blood test. It takes longer and helps you sober up.” I tried refusing the breathalyzer and asking for the blood test. The officer said they’d have to drive me to the Valley for it. It would take a long time and meant I’d be in jail several hours longer. I asked if I could have water. No. They needed a decision. I waffled for what could have been five minutes or what could have been an hour. There was no way of knowing. He told me if I took the breathalyzer I could go home. I’d never been in trouble before. I believed him. I also desperately wanted water and figured I’d have to go to the bathroom soon, anyway. Somewhere distant, almost vacant, I heard Nick’s words and changed my mind again.

“I want the blood test.”

The cop grew impatient at this point and signaled for his partner. Time to put the clamps down. The partner stood over me. “Just do it and you can go home,” he urged. Finally, I agreed. I stood, followed him to the breathalyzer and blew into the tube.

“Wow,” he said. “You blew over twice the legal limit.”

They booked me. I stripped out the laces of my shoes and emptied my pockets. License—which I never saw again. Wallet—everything taken out and wrapped in a rubber band. The cop escorted me through the gate, took my picture, fingerprinted me (which took several tries to complete) and put me in the cell. I still thought I was going home and yelled several times, through the bars, to the officer at the desk. “They said I could go home. I need to go home.” The words came out slurred and indecipherable. “Let me out of here. He told me I could go home.”

“You can go home in the morning. Now quit talking. Go to sleep.”

I protested a few more times and walked away from the gate.

I was alone in the cell. For this, I was grateful. I was coming down from my drunk and only wanted to sleep. Three sets of bunk beds. I took the top one, furthest from the gate. “Lord,” I prayed, “thank you for your mercy. For loving me and getting my attention. Forgive me for what I’ve done. Thank you I didn’t hurt anyone. I love you, God. For who you are, not what you do for me.”

Perhaps it sounds strange I would be praying, but it shouldn’t. Men often pray when they are in trouble, and I was. When I got up to use the urinal in the middle of the night, I noticed another man sleeping on one of the bunks.

After a few hours of restless half-sleep, I woke up panicked. I remembered I had to work that day. What was I going to do? I asked to make a call, and one of the officers escorted me to the phone. It was already seven in the morning and my boss Greg would be there by eight. I didn’t know if the caller ID at work would show up as “Los Angeles Jail” or not, but I didn’t have a choice. I left a message, saying I wasn’t feeling well and needed to take the day off. Told him I’d see him tomorrow. It was a lie, but technically I wasn’t feeling well. I was hung over and in jail—that’s about as bad a feeling as one can have.

I returned to my cell. I said hello to the other man. He’d been kind enough to save me a tray of breakfast: carton of orange juice, pastry of some kind and a granola bar. I thanked him but wasn’t in the mood to eat. Moments later, an officer escorted a group of men into the cell.

This is what I’d been afraid of. There were eight or nine of them, looked like they’d been taken straight from the beach. Several were shirtless, shoeless, dirty and unkempt; they entered the cell loud and rude and forced their way onto the bunks, paying no attention to me or my cellmate. The one who looked to be the leader—tanned, no shirt, I guessed he’d spent many afternoons in Venice—snatched the breakfast tray from the floor. He emptied the juice carton in three gulps and tossed it in the urinal. I sat quietly next to my cellmate, not wanting to draw attention. The men shouted to the officers outside; they shouted to each other. I’d grown used to the quiet cell; there was safety in it. Now it was gone.

How much longer would I have to stay here?

A half-hour later, the officer opened the gate. He ushered the men from the cell. “The judge will see everyone now.”

“Do we go, too?” I asked my cellmate. Shades of panic.

“No.”

The men strutted from the cell, leaving us again with silence.

I had several questions for my cellmate. He seemed to have experience with this kind of thing. I didn’t know how it worked. Would the police take me home? Or at least back to my car?

“They don’t give rides,” he said.

He had heard me being interrogated earlier. I didn’t remember him because I was too drunk. “Was it true what you said about being at a church dinner?”

“Yes.”

“You were pretty hammered. You kept asking for water.”

The cops had pulled him over the night before and found several warrants outstanding. He had called the public defender and in the meantime was waiting for his girlfriend to bail him out.

“What time do you think they’ll let me go?”

“Probably noon. Maybe a little earlier.”

He was right. Shortly before noon, the officer called my name and announced I was being released. I said goodbye to my cellmate and

thanked him for everything. The officer let me out of the cell, then buzzed me through the gate. I signed for my belongings…rubber band tied around my wallet. Shoelaces. Keys. Where was my phone? Had I lost it? And where was my watch?

Lost watch. Insignificant, but still a regret. Money down the drain. Phone? No telling where it was. Hopefully it was in the car, but at that point, who knew?

I was wearing my Pumas. That was fortunate. Typically, I’d wear nicer shoes to a dinner party, but Angela had a shoes-off policy in her apartment and I didn’t think it mattered which ones I wore. Unfortunately, the laces of both were frayed at the tips. The thought of sitting in the lobby of the station or the steps outside to put them in made me nauseous—I wanted to get away from there as fast as possible. I looked at the pink temporary license the cop had given me (court date set for August 6), returned it to my pocket and started walking, shoes slipping and rubbing with every step against my heels. I didn’t want to stop, though. It would remind me of everything that had happened. At least walking permitted the distraction. How far was it? I looked for a street sign. Culver and Centinela. Probably three miles, maybe more. I kept going.

Upon my release, I’d asked one of the officers about my car and he told me it was parked at Palms and Clarington. I hoped it was there. I was already resigned to my phone being lost. I’d have to go to the carrier that afternoon and deal with it.

My God, this is my life now?

I walked half a mile but couldn’t go further. I sat on the steps of a closed building and put in the laces. It took ten minutes. It also forced my mind to slow down and think about things. I was thirsty and hung over. My eyes were dry. I’d slept in my contacts and woke with them sticking to my eyeballs. I tried to make myself yawn to moisten them. I felt miserable in every way—physically, emotionally, spiritually and mentally. It couldn’t get much worse, and it was my own rotten fault.

Not to mention it was sweltering outside. The sun was already blazing and it wasn’t noon yet. I walked three miles and stopped at the Starbucks on Overland for coffee and a scone. Nearing Palms and Clarington, my pulse started racing. I remembered Thursday was street cleaning day. My car had been parked in a restricted zone for two hours. Forget about the phone. I wasn’t sure I was going to find my car.

It was there. One couldn’t miss it, the only car parked on the south side of the street, like a partygoer who hasn’t realized the other guests have long since left. Well, at least it wasn’t towed. A $50 ticket on the windshield—at this point, just add it to the bill, which was surely going to get a lot higher.

How high it would eventually get, I couldn’t have known then.

I opened the car door, suffocating on the heat coming from inside. I saw my phone resting on the seat. Huge sigh of relief. One headache I had avoided, though it burned my hand when I picked it up. Eleven missed calls, a dozen texts and several emails. I’d worry about them later. Right now, I needed to get home. I put the parking ticket on the seat beside me and drove the three blocks to my place.

Angela was worried sick. She and Nick were the eleven calls and dozen texts. She had regretted letting me drive and called several times. When she didn’t hear from me, she got nervous and called Nick, who’d been at the tavern with us. Now, twelve hours later, she was a borderline basket case, freaking out.

I told her what happened, that I’d spent the night in jail. She didn’t speak for several seconds. She said she was busy at work but would call me later, and if there was anything I needed (specifically, a ride) to please let her know. I said I had my car for now, but might be taking her up on the offer soon. I called Nick. He was the only one I knew with a DUI. He didn’t think I was that drunk at the tavern, at least not that he’d noticed. He asked what I blew. I wouldn’t tell him. It was too shameful. I asked about his lawyer. Nick had gotten off with a reckless driving charge.

The week after his arrest, Nick came to our Bible study distraught, a far cry from his usual upbeat, fun-loving self. When we separated into men and women’s prayer groups, he confided with us. He’d hit a post after leaving a party and spent the night in a Pasadena jail. I prayed for him. “God, I can’t count the number of times I’ve done the same thing. I’ve messed up more times than I can remember. Would you comfort Nick during this time? Not to excuse what he’s done, but would you use it to get his attention, all the while showing him that you love him? May what he’s going through bring him closer to you.”

Later that night, Ed K., a new Christian in the group, told me, “I appreciated your prayer. I think we can all relate to what he’s going through. Maybe not drinking, but things we’re ashamed of.”

Now I was the one calling Nick for advice. I assumed he would tell a few people at church and the Pacific Crossroads rumor wagon would begin its course, but it was the least of my worries. I asked about his lawyer—if he’d been happy with him, the job he’d done…and finally, the big question:

“I paid $4000,” he said.

“$4000?” My heart dropped like a brick. “$4000?”

“You need a lawyer and this guy’s good.

I couldn’t get the number out of my head. I was already in bad shape financially. My salary at work was next to nothing. I’d spent what little savings I had on acting expenses for so long. I moved into a place of my own a year ago and the rent chewed up most of my paycheck. To my surprise, Nick told me that a close friend of ours, Allison, had been arrested twice for DUI.

“Allison? I had no idea.”

“Hardly anybody does. You should talk to her. She won’t mind. She helped me when I was going through it.”

I called her. She knew I was going to San Jose that weekend and asked if I was excited. “I actually called for a different reason.” Speaking gingerly, I recounted the events to her.

“Oh, Michael. I am so sorry!”

“Don’t be sorry. It was my fault. I made a terrible mistake. The worst mistake of my life.”

She spoke at length about her DUIs. I was impressed by her willingness to share such potentially embarrassing details. She’d lost her license for thirty days. “The Hard 30,” she called it. Surprisingly, she spoke of that period with affection. She’d taken the bus to work and it led to a sort of spiritual awakening for her. She hired a top of the line attorney and paid him $7000. My spirit sank lower. I was quickly finding out—there is always a new depth to how low our spirits can sink.

“If there’s anything I can do, please don’t hesitate to ask.”

“I may need some rides in the near future,” I said half-jokingly, an attempt at levity in darkened circumstances.

I couldn’t talk to anyone for a while after that. I was feeling sick, overwhelmed with repulsion and dread, adding to the shame and memory of the past twelve hours. What was I going to do? It was my own fault. I was the one who chose film and music and writing pursuits all these years, foregoing a career for myself. Now, looking at financial shipwreck, I was screwed. An email showed up on my phone. My friend Jon. We did a Bible study together every day and had just started the book of Acts. I sent him a brief message explaining what happened but told him I couldn’t talk about it at the moment. I’d explain everything later. I closed my eyes. There was one more call I dreaded, but I needed at least an hour before making it. I had to spend some time in silence.

When I called, my father answered the phone. Typically, our conversations go like this:

Hey, boy. What’s going on out there in sunny California?

Ah, nothing new.

Okay. Here’s your mom.

This time he said, “Your mom’s outside working in the yard. Give her a call in thirty minutes or so.”

“Actually, I need to tell you something.”

I’m sure it was a bit much for my dad to take in. On second thought, I doubt it. My brother got a DUI a few years earlier. After all my brother and I have put him through, I’m sure my dad is shock-proof by now, though he probably wouldn’t admit it.

My mother called shortly aft

er. I assumed he had told her, but when I said hello it was obvious she didn’t know. “How are you?” she asked, more chipper than expected.

“Did Dad tell you?”

“Tell me what? He just said you had gotten a ticket.”

I couldn’t figure that one out. “No, I didn’t get a ticket.”

When I went home for Christmas each year, I drank. My brother-in-law and I would go to the store and load up on beer or Jack Daniels. It was vacation. That’s what they were made for. When my mother asked if I drank too much, I defended myself. I wasn’t getting drunk (though I would often have a beer for lunch or Jack on the rocks in the middle of the afternoon). “There’s nothing to worry about,” I assured her. But I knew she was concerned.

This time she had the right to ask, and I couldn’t defend myself. The burden of proof was on me, the verdict sitting on my bedside table in the form of a pink arrest slip with “DUI” stamped at the top. Any charge she brought against me I had to accept with a contrite spirit, which wasn’t difficult. I was contrite. I felt broken in a hundred pieces. There wasn’t the pride with which I usually spoke to her.

The only time I get that way is with family. With friends, I don’t defend myself. But when I’m talking to my parents or siblings, the hair on my arm sticks up. I feel the warmth in my face and usually resort to saying something arrogant and proud and regret it for the rest of the day. I don’t understand why. Maybe it’s from years of having to defend myself and the choices I’ve made, from making a mess of myself in college, transferring in and out of four different schools, traveling the country with everything I owned in my car, moving to Seattle to play in a rock band without any musical experience or knowing anyone there, to finally moving to Los Angeles at age 30 to become an actor. Maybe I speak with a haughty tongue because I feel I have to prove myself to them. Maybe it’s bitterness toward my hometown. Whatever the case, it usually happens this way: I pray for calm and gentle speech before calling, but after a few minutes I become defensive, hair standing on end, and say something stupid and kick myself disgustedly for hours afterward.

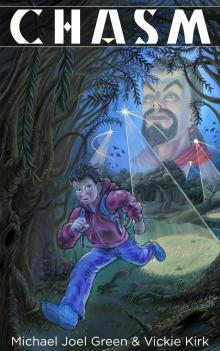

Chasm

Chasm Arresting Grace

Arresting Grace