- Home

- Michael Joel Green

Arresting Grace Page 4

Arresting Grace Read online

Page 4

She was wearing white jeans and platform sandals. A light-blue blouse. I was certain we were both nervous and gave her a hug right away to ease the tension. I told her I’d already checked in, so we could get on the road.

It was an hour’s drive into the city. She still made the trip often, but missed living there. When she was working at the corporate firm, she lived in a downtown apartment overlooking the water and Bay Bridge. It was a haven for her. At the time, she was painting regularly and had put two of her paintings on display in the apartment. When she moved in with her parents, she sold most of her furniture, including her bed and favorite down comforter, which she regretted the most.

The conversation was natural and comfortable, as it had been in L.A., but I was one day removed from being arrested and spending the night in jail as a criminal. It would have been impossible for me to overlook that. It was always in the back of my mind, preventing me from speaking freely and completely at ease. I knew there was a slight heaviness to the conversation. Then she asked the age question.

I didn’t know how old she was. I had a general idea. Sonia was 31 and they’d gone to school together. I took a slow breath.

“I’m 38,” I told her.

“Really?” She paused. “Sonia must have lied to me. I thought you were 35, maybe 36.”

I wanted to sink into my seat. One strike so far. In an hour or so, I’d be giving myself another one. At this rate, I’d be headed home before sundown.

We decided to go to the Mission District. She attended church there when she lived in the city and wanted to take me to a French bakery, Tartine, where she often ate after service. Now, depending on how one chooses to look at it, driving in San Francisco is either an exercise in patience or a lesson in futility. Whatever the case, we couldn’t find parking and circled the neighborhood several times before finding a space. On our walk to the bakery, we passed a tattoo shop. I asked if she had any.

“No. Do you?”

“I never found one I liked enough. I’ve been as far as sitting in the chair, having already paid, but backed out because I didn’t like the design well enough.”

“What was it?”

“A Celtic cross.”

“Oh, that’s so boring. Everyone has that.”

I felt the need to defend myself—or the cross, that is. I agree, they are cliché, but there’s a tattoo shop on Venice Beach my brother-in-law and I found several years ago with a Celtic cross unlike any I’d seen. A simpler design, not as many floral knots. My brother-in-law got it. I backed out. I didn’t like it as much as he did.

“If you were going to get a tattoo, what would it be?”

She laughed slightly. “You’ll think it’s stupid.”

“No, I won’t. What is it?”

“You’ll laugh.”

“No, I won’t. Besides, you’ve got to tell me now. You’ve built up the excitement.”

“When I was in college, I wanted to get a tattoo of a pair of jeans.”

“Jeans?”

“Don’t laugh.”

“Blue jeans? Why not a pair of khakis, maybe Dockers?”

“That’s why I didn’t want to tell you.”

“Just the pair of jeans? No legs inside, no feet dangling from the bottom?”

“Nope. Just jeans.”

“What about a pair of sneakers at the feet?”

“Just jeans.”

“Where would it be?”

“On my ankle, of course.”

“You’ll be the only one with a pair of Levi’s on your ankle, that’s for sure.”

My heart grew heavy at that point. I knew I needed to tell her. Also, the memory of the arrest and being in jail kept flashing to mind. It took my focus away from her and I didn’t want that to happen. At Tartine, the wait for an outdoor table was an hour long. Inside was communal seating—we could sit right away if we shared a table. “That’s fine, I said.” The talk would have to wait. We ordered and sat across from an older woman, holding two large orders of bread pudding in front of her. I excused myself to the restroom.

When I returned, Jessie and the woman were speaking as if they’d been friends for years. The woman, Carol, had been a schoolteacher for thirty years and recently retired to Marin County. She offered Jessie a bite of her pudding (“You have to try these blackberries!”) and plopped a huge spoonful on her plate. Jessie took a bite, then offered me one. Carol was waiting for a friend, who was late, and they were going to go see a foreign movie, “I Am Love.”

“Maybe we should see a movie,” Jessie suggested.

“Are there any horror movies out right now? I’ll check on my phone.”

Carol’s friend Ron arrived and we introduced ourselves. I couldn’t tell from the way they interacted if he was a boyfriend or not. Jessie and I joked that Carol was making him see a romantic, foreign film as punishment for being forty-five minutes late. We finished our lunch and said goodbye to them. Carol gave Jessie a hug as we left. I knew it was time to tell her. It was burning inside me and that’s usually how I know these things.

With her job, she sees brokenness on a heightened level every day—children with broken bones, drug-addicted parents. Anything imaginable, she has probably seen. But I didn’t know: How would she react to this? It’s one thing to have empathy for clients, a fragment of society far removed from the church and those within it. I knew she had a big heart and her spiritual gifts were compassion and understanding, but those were for the kids she represents, not the man hoping to date her. I had no right to presume that level of empathy. Common sense would say to keep people who’ve been arrested at arm’s length. Serve them, pray for them, but don’t let them inside one’s home. Regardless, it was burning inside me and I had to tell her. We left the restaurant and turned up the sidewalk.

I had listened to a sermon the night before on the life of David, focusing on Psalm 51. The pastor told a story of Charles Simeon, an 18th century preacher, who reputedly prayed and studied the Bible every morning from 4 to 8 a.m. On his deathbed, he wanted only one verse read, over and over—Psalm 51:17. I had written, for no reason other than to remind me, “51:17,” on my hand, next to a scar I’ve had since childhood, and forgotten to wash it off. The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit. A broken and contrite heart, O God, you will not despise. Jessie saw it and asked what it meant. I told her, then followed it by telling her of my drunk driving arrest.

If I was sold on this woman before, I was all in now. The woman was so gracious, so understanding. Not that she didn’t ask about it—she did, and we discussed it at length—but there wasn’t the judgment I expected, the turn-off I knew would be coming. We sat at the park among hundreds of others, different enclaves of different cliques of society, some playing sports, some tanning and some drinking. I spoke honestly of the mistake I’d made, how I’d not been letting God into that area of my life. Going out too much. Maybe not getting drunk but drinking too many nights of the week. She said she noticed I was more subdued this time than in Los Angeles, that my words seemed more weighted. Now it made sense.

As we talked that afternoon, getting to know each other, a thought struck me. All my life, whenever I’ve messed up (and there have been too many times to count), my repentance has been to beat myself up for it until enough days have passed that I feel it’s accounted for. I’ve known the Gospel all my life. I’ve followed Jesus for fifteen years, but I still lose sight of grace. If I can criticize myself and tell myself what a horrible person I am, it’s my way of atoning. In that moment, sitting in the park with hundreds of other people on a hot summer day in July, I realized, “God wants to love me right now.”

Despite what I’d done, He wanted to love me. Not only that, He wanted to bless me that weekend. Unlike the thousand times before, when I proclaimed to believe in grace but put myself through the gauntlet of self-inflicted punishment, as I sat with this kind, compassionate, gorgeous and delightful woman, I told myself, “And I’m going to let him.” It freed me. The memory was still

there, haunting me on occasion, but the weight was lifted, and we were able to speak openly and honestly and enjoy each other’s company that afternoon and the rest of the evening. We left the park and went to Twin Peaks, a forty-minute drive. It turned out to be too windy to stay, but while we were there, I told her what a huge baseball fan I was and she suggested driving to the ballpark to find tickets to that night’s game. I couldn’t believe the grace I was receiving, her driving all that way for me because I said I liked baseball. On the way to the stadium, we talked about God, faith, the difficulties of the Christian life, ghosts (She saw one when she was thirteen, that of her grandfather), homosexuality and whether we thought it was innate or chosen. The afternoon flew by. We couldn’t find parking anywhere near the stadium (The best offer we received was from a homeless man who tried to sell us a wadded-up parking ticket for $25, undoubtedly from the previous night’s game) and decided instead to visit her favorite Japanese restaurant in the city. She’d not eaten there in over a year, but the waitress still remembered her and gave her a hug. How could she have forgotten?

That night, it was cold and lightly raining. We decided to see a movie. We couldn’t find a horror film showing in the theatres, at least one we’d heard of or that sounded decent. On a lark, we decided to see “Twilight.” We’d been making fun of it the past couple of weeks. Neither of us could understand the fascination, but we admitted it looked deliciously cheesy. Walking down the steps of the sidewalk, she put her arm through mine and we laughed at what we were about to do. We drove to a theatre in Japantown and bought tickets. She went to the restroom, while I bought sodas and a large box of SweetTarts. We stepped into the theatre before the trailers started.

I was at that point when a man decides whether it’s time to hold hands for the first time or not. She’d put her arm through mine earlier. We seemed to enjoy the other’s company. Was it too soon? Right away, I saw the problem. The theatre’s seats were arranged with large wooden platforms in between the armrests, ten to twelve inches apart. There were a few seats without the annoying platform, but the tickets were assigned seating so we couldn’t switch. We sat down and immediately I knew it wasn’t going to work. I felt I had to shout to speak to her she seemed so far away. No way would I be able to hold her hand with this barricade in the way. I saw two seats without the platform, still empty. I took her arm and we shuffled over to fill them.

Blast it. A cluster of teenage girls walked in seconds after we sat. Please don’t have our seats. I peeked over and saw one of the girls, wearing an Edward Cullen t-shirt, looking down at her ticket, then at us, with a confused expression. Again, she looked at us, then to her ticket, too nervous to say anything. Good, be nervous. Now go find somewhere else to sit.

“Excuse me…”

Rotten luck. We returned to our seats, the platform now seemed an ocean separating two islands. So much for holding hands. We made small talk before the movie began.

“What’s your favorite worship hymn?”

“‘Abide With Me,’” she answered.

“I don’t know that one. How does it go?”

“I’m not going to sing it.”

“Just a couple of lines.”

“No. I’ll do it later when there aren’t any people around. What’s yours?”

I couldn’t choose a favorite. It was either “All Creatures of Our God and King,” “It is Well With My Soul,” or “Be Thou My Vision.”

The trailers ended and the movie began. The first scene opened in an orchard, with the two lovers lying in the grass, declaring their love for each other. The male vampire looked deeply into the girl’s eyes and spoke the first words…

We laughed out loud. It was delightfully horrible. The more the actors talked, the harder it was for us to smother our laughter. “Let’s get out of here,” I whispered, reaching for her hand. “We’ll sneak into something else.”

We left the theatre, still laughing, taking turns quoting the hokey dialogue we’d heard, exaggerating it for humor’s sake.

“That was soooo bad,” she said.

I hadn’t planned on sneaking into another movie. The problem was only one other movie was showing in our section of the theatre. Otherwise, we’d have to show our tickets to one of the attendants. To our surprise, the movie was just beginning. The title: “I Am Love.” We smiled.

“I wonder if we’ll see Ron and Carol,” she said.

We entered the theatre. If we could only find two seats side by side without the ridiculous platform. Bingo. Top row, aisle seats. Very unlikely anyone would choose those seats unless the theatre was full… hardly the case with this movie, subtitled in Russian. Surely none of the Twilight groupies. Our eyes widened. A group of six women, all speaking what sounded like Russian, entered the theatre. My breath tightened. What side would they choose?

The opposite side. We breathed sighs of relief. The movie started, the doors shut. We were safe.

I think Jessie enjoyed the movie more than I did. Or, maybe I should say, she watched it more closely. It was hard for me to concentrate. Sitting with our shoulders touching, her arm lifted on the armrest (as if scorning me for not grabbing its hand), she fed me SweetTarts throughout the movie. I never held her hand but it was the next best thing. She’d hand me a SweetTart, more gently each time, and our fingers would slowly rub together, lingering, then separate. I’m surprised I didn’t get sick from the number of SweetTarts I ate; though, had I, it would have been worth it.

The movie was about a repressed housewife who meets a charismatic young artist and cheats on her husband. On the drive home, we talked of marriage and dating and the Song of Solomon. She asked if I could ever cheat. One of her father’s best friends had recently committed adultery and returned to Korea to live with his mistress.

“I’d like to believe I wouldn’t,” I answered. “But I think it’s as soon as we start believing in our own goodness that we’re most likely to fall. I want to guard against any pride that allows me to think that. Solomon was given more wisdom than any man in history but ruined his life with 700 wives and 300 concubines. Why is that? I don’t know, but I think it shows any of us can fall.”

The next day, she picked me up and we went to her church. The church was a newer church, a plant of a larger one based in L.A. Its congregation was a very young one, with an inexperienced band, somewhat sloppy. I realized I have a tendency to judge other churches. Rankin is a dynamic and powerful preacher. Chris, our worship director, has a doctorate from Julliard. I often think PCC is the only church that can offer a powerful worship service and hold other churches in light of its comparison. When they don’t measure up to my standard, I shut my ears and eyes. And heart. That morning, I rejected this tendency. “God,” I prayed, “meet me where I’m at, in this moment, with all the confused emotions and uncertainty of my life. Meet me here.”

As luck would have it, the pastor, Ken, preached on Luke 18. The beggar and the rich man at the temple. The rich man trumpets his good deeds before the Lord, while the beggar pleads with God for forgiveness. Pastor Ken said, “We should all see ourselves as beggars before the Lord.” Somewhere along the way, I’d stopped seeing myself in that light. That is, until that week, when I’d been brought lower than ever before, fallen worse than imaginable. The sermon was exactly what I needed. I was the poor man at the temple. All my years of serving in the church…who cares? The dedication, the deeds—they all count as rubbish. When one has fallen, there are no service projects or ministries to hang his hat upon. There’s only this, the words of the beggar: “Have mercy on me, O God, a sinner.”

God met me exactly where I was in the moment, gave me the words I needed to hear, even if it was in a young but growing church four hundred miles away. After the service, Jessie and I drove to Zachary’s Pizza near Berkeley. Several of my friends had recommended it. After we parked, she changed out of her platform sandals because they were digging into her heels and put on a pair of flip-flops.

“You seem a lot taller now. How

tall are you, anyway?”

“5’10. Well, 5’9 ½. I put 5’10 on my acting resume.”

She told me about her family. Her grandfather had been a wild man. Didn’t speak a lick of English but loved going to Vegas and Reno to see the lights and play blackjack. “I was crazy about him. He was so much fun.” She had a grandmother, her father’s mother, who still lived in Korea. Jessie had visited her a few months back; they thought she was near the end. I told her about my grandmother and the time leading up to her passing. We were scattered at the time. My sister’s family was in Texas. Stephen was in Colorado and I was in Seattle. Granny was living with my parents. Pancreatic cancer had spread throughout her body. She was in a semi-coma. Each of us, during separate weeks, was able to go home and see her. My sister visited soon after her third child, Anna Grace, was born. Granny came out of her coma that weekend and was lucid their entire stay. She held Anna Grace in her arms and, according to my sister, had a glow about her…almost angelic, and definitely touched by heaven. There was a peacefulness written upon her face.

I went home the following week. I’d written a song for her, about being at the end of one’s life (or as best I could imagine it) and saying goodbye to friends and family. She was lucid and awake when I was there and able to sit for an extended time in the living room. I sang the song for her. That afternoon, before leaving for the airport, I lay in bed with her and started crying.

She said, “If I never see you again, I want you to know how much I love you.”

What would it be like—what will it be like—to say goodbye to this life, knowing our time is over? Will we be able to do it with joy, or will we look back with regret?

Jessie pronounced herself full, unable to eat anymore. She’d left two pieces—one sausage lover’s, one spinach and mushroom—and I finished them both. I couldn’t let them go to waste. The pizza was too good to eat as cold leftovers.

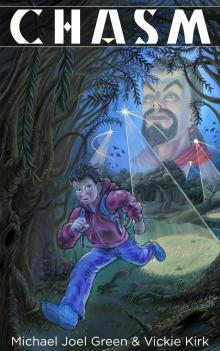

Chasm

Chasm Arresting Grace

Arresting Grace